1964: The United States Central Intelligence Agency spends $20 million in Chilean elections to defeat the Marxist candidate, Salvador Allende. Per voter, this is an amount larger than what the 1964 Goldwater and Johnson campaign spent in U.S. elections — combined. This campaign included propaganda such as a radio ad with machine gun fire, followed by a woman’s cry: “They have killed my child — the communists.” The CIA’s candidate, Eduardo Frei, beats Allende 56 percent to 39 percent.

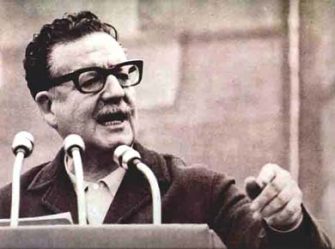

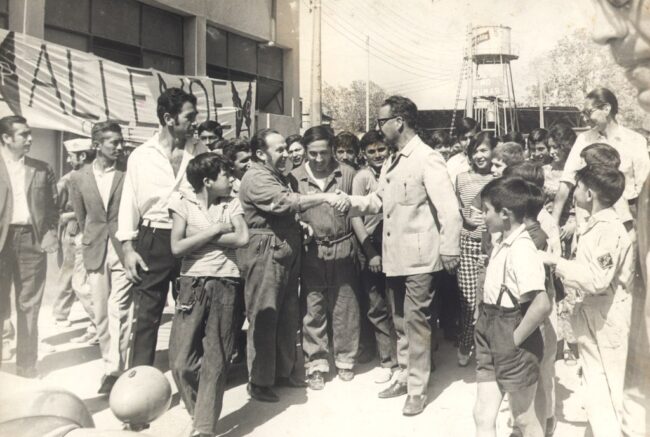

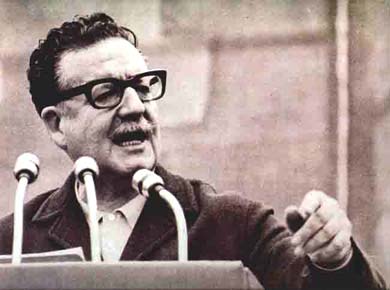

Salvador Allende

January 1970: Salvador Allende is nominated as the joint candidate of a new coalition of leftist parties, the Unidad Popular, in English, Popular Unity. He will run against two other candidates. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) provides at least $400,000 to anti-Allende news media in Chile in an effort to stop his election.

June 1970: President Richard Nixon’s National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, says in private, “I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go Communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people.” U.S. corporations have about $1,100,000,000 dollars (one-billion, one-hundred million dollars) invested in Chile.

September 1970: Allende wins 36.2 percent of the popular vote, placing first among the three candidates. Because he does not win an absolute majority, his victory is confirmed in a special session of Congress, as called for in the Chilean constitution.

September 15: Nixon, Kissinger, and CIA director Richard Helms meet. From Helms’ handwritten notes of Nixon’s remarks: “One in 10 chance perhaps, but save Chile! . . . not concerned with risks involved . . . $10 million available, more if necessary . . . make the economy scream . . .” One White House options paper discusses ways of assassinating Allende.

October 1970: Army commander in chief Rene Schneider is shot and killed by right-wing sectors of the Chilean army. They were attempting to spark a military coup to prevent Allende from coming to power. The weapons had been provided by the CIA, according to later testimony before a U.S. Senate committee.

December 1970: The Chilean government begins a program to guarantee a half liter of milk per day for all the children of Chile. A people’s health train with doctors and dentists gives free treatment to peasants during a 35-day tour of southern Chile.

January 1971: The government begins to nationalize large industries beginning with the German-owned coal mines in the south, which provide 80 percent of the country’s coal. The government intends to use profits from nationalized industries to fund its social programs. A U.S. official says privately that “The best way to get at Chile is through her economy,” and says that “the U.S. will apply quiet pressure along economic lines and encourage other countries not to invest in Chile.” The U.S. ambassador to Chile has said privately, “not a nut or bolt [will] be allowed to reach Chile under Allende.” The World Bank (with Robert McNamara, former U.S. Secretary of Defense, as president) refuses to lend any money to Chile under Allende, even for things like fruit-growing projects that it had supported in the past.

February 1971: President Nixon says publicly that the United States will not interfere in the internal affairs of Chile:

We deal with governments as they are. Our relations depend not on their internal structures or social systems . . . We are prepared to have the kind of relationship with the Chilean government that it is prepared to have with us.

April 1971: Popular Unity candidates win 51 percent of the vote in municipal elections.

May 1971: As a result of rent limits, price ceilings, and wage hikes, workers have received an increase of 40 percent in real wages since the new government came to power.

July 1971: The Chilean Congress votes unanimously to nationalize the copper mines. The mines are owned by U.S. corporations. In the last 60 years, these corporations have taken profits out of Chile worth one half the total amount of wealth produced in Chile over the last 400 years. Later, Allende explains before the United Nations:

Those same enterprises exploited Chile’s copper for many years, in the last 42 years alone taking out more than 4,000 million dollars in profits although their initial investment was no more than $30 million. In striking contrast, let me give one simple and painful example of what this means to Chile. In my country, there are 600,000 children who will never be able to enjoy life in a normal way because during their first eight months of life they did not receive the minimum amount of protein. Four thousand million dollars would completely transform Chile. A small part of that sum would ensure proteins for all time for all children of my country.

Most of Chile’s textile, iron, and automobile industries and 60 percent of the banks have been nationalized since Allende took office.

September 1971: International Telephone and Telegraph’s (ITT) 70 percent ownership of the Chilean telephone industry is taken over by the government. The countries of Ecuador and Guyana initiate moves to take over the holdings of foreign corporations.

A 1972 anti-ITT cartoon from Chile. Source: Evgeny Morozov, Twitter

December 1971: The government completes the first phase of a land reform program. About 10 million acres are redistributed in cooperatives to poor families.

Fidel Castro visits Chile to show his support for the Popular Unity government.

Anti-communist women march in downtown Santiago beating empty pots and pans to protest the government.

January 1972: The U.S. Export-Import Bank cuts off all loans to Chile, even though the United States admits that Chile has always paid its debts on time. Almost all trade between Chile and the United States depends on short and medium term loans. Forty percent of Chile’s exports come from the United States. Following the cut-off of Ex-Im Bank credits, all commercial banks follow suit and cut off credit to Chile. The cut-off amounts to an economic blockade of Chile. Chile cannot get spare parts for machinery, buses, or trucks. The economy begins to develop serious problems. By late 1972, roughly one-third of all the diesel trucks at the copper mines, government-run buses, and private micro-buses can’t operate because of a lack of spare parts.

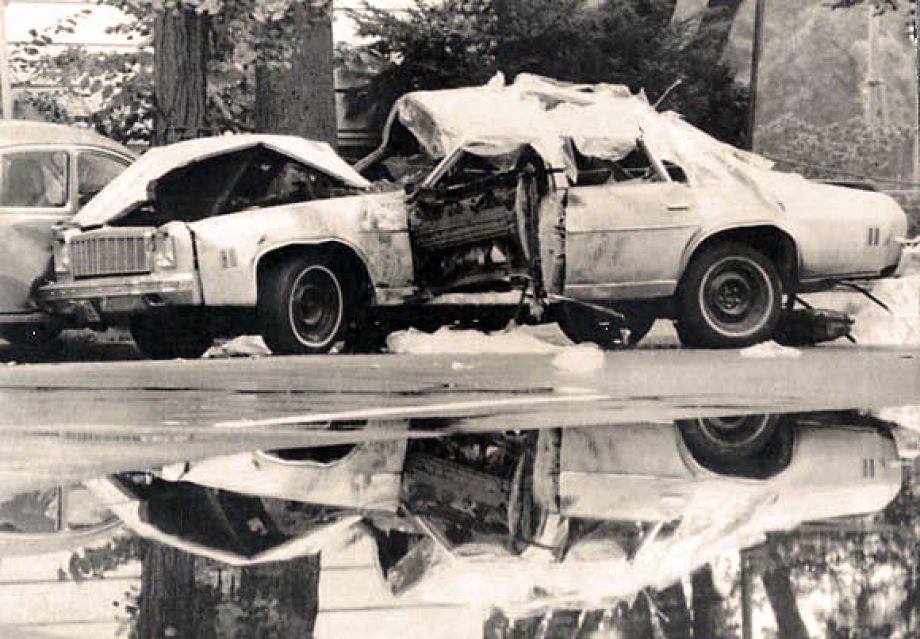

March 1972: According to memos released by the columnist, Jack Anderson, ITT has been trying to bring about the overthrow of the Allende government. The memos link ITT to the assassination of General Schneider and show that ITT offered large amounts of money to the CIA in their efforts to destabilize the country. Anderson quotes memos from U.S. Ambassador Nathaniel Davis regretting that “Chile is not yet on the brink of a showdown.” He writes that before ITT is likely to get its coup, public opposition to Allende would have to become “so overwhelming and discontent so great, that military intervention is overwhelmingly invited . . .”

October 1972: The opposition holds a “March for Democracy,” calling for action and not words against the Allende government. The Truck Owners’ Federation, merchants, professional unions, and the Chilean Association of Manufacturers go on strike. The strike is preceded by a large influx of dollars. In response to this offensive by the owning classes, workers, students, and peasants mobilize and form neighborhood committees based in the industrial zones to take over factories and maintain production, distribution, defense, and health care throughout the country. The October strike costs Chile between $100 and $150 million.

December 1972: Allende is in New York to address the United Nations. Nixon refuses to meet with him.

March 1973: Despite the U.S.-directed disruption of the Chilean economy, the Popular Unity government wins 44 percent of the congressional vote totals, compared to 36 percent in 1970. This is the first time in Chilean history that a government increased its vote totals in midterm elections.

Early September 1973: Bread shortages are developing. Chile requests credit to buy 300,000 tons of wheat from the United States. The Nixon administration refuses.

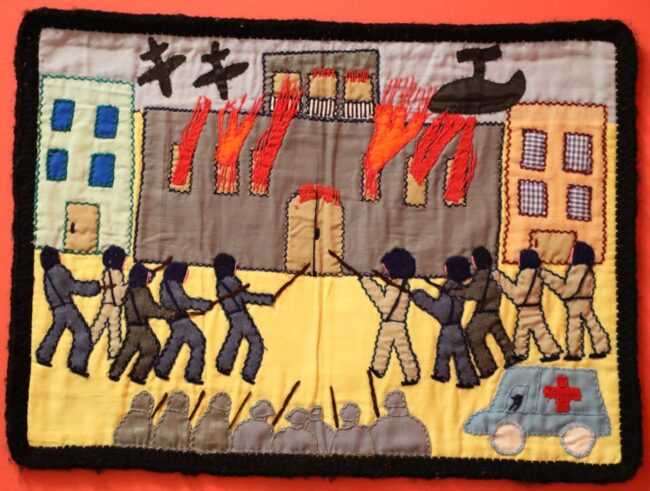

The Coup, 1986, embroidered textile. Courtesy of Francisco Letelier and Isabel Morel Letelier. Source: Museum of Latin American Art

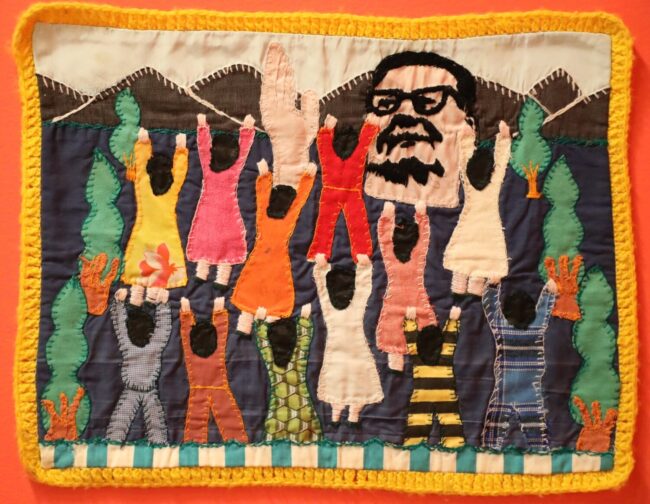

September 11, 1973: The Chilean military launches a coup. The Junta, headed by commander in chief of the army, General Augusto Pinochet, declares itself the government, proclaims a State of Internal War, imposes martial law and carries out a brutal campaign to destroy areas of resistance. At least 10,000 Chileans and foreigners are held in the national stadium. (In 2011, the Chilean government acknowledged that more than 40,000 people had been murdered, disappeared, or tortured by the Pinochet dictatorship.) Allende and his aides die defending the national palace — they had refused to surrender. (Some were killed, Allende committed suicide.) In his last radio address, Allende says,

Probably Radio Magallanes will be silenced, and the calm metal of my voice will not reach you: It does not matter. You will continue to hear me, I will always be beside you or at least my memory will be that of a dignified man, that of a man who is loyal.

Soldiers burn books and a poster with an image of Che Guevara during the 1973 coup in Chile. Source: Public domain

The country is closed to the outside world for a week. No one is allowed out or in; all borders and international airports are closed; international communications are cut.

Marxist political parties are outlawed, leftist newspapers, radio and TV stations closed. Congress is closed. The constitution is abolished. All mayors and locally elected representatives are removed and replaced by active or retired military officers. The largest labor union, with 800,000 members, is outlawed.

The Junta makes an effort to erase all traces of the popular culture of the Allende years: public burning of books, posters, newspapers; all murals and wall paintings obliterated; the leftist poet Pablo Neruda’s home is ransacked and his manuscripts disappear; use of the term compañero to address one another is outlawed, certain musical instruments associated with the “New Song” movement are banned. The heads of all universities are replaced with military appointees.

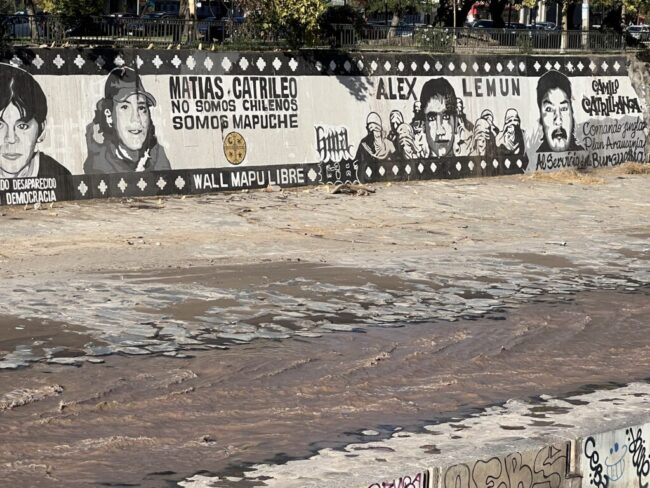

The Mapocho River runs through Santiago where bodies were found after the 1973 coup. This mural features Indigenous resistance fighters. Source: Marc Cooper, Truthdig

The Junta returns control of more than 350 factories nationalized by the Popular Unity government to previous owners; worker participation and management is abolished; wage increases are canceled. U.S. companies announce interest in reinvesting in Chile. The U.S.-dominated InterAmerican Development Bank grants Chile a $65 million loan. U.S. banks begin lending millions of dollars to the Pinochet regime.

October 5, 1973: The Nixon administration grants $24.5 million in wheat credits to the Junta in Chile.

“It is clear,” said a U.S. Senate committee report, “the CIA received intelligence reports on the coup planning of the group which carried out the successful September 11th coup throughout the months of July, August, and September 1973.”

September 17, 1974: President Gerald Ford: What the United States did in Chile was “in the best interest of the people in Chile and certainly in our own best interests.”

Remembering Salvador Allende, embroidered textile. Courtesy of Francisco Letelier and Isabel Morel Letelier. Source: Museum of Latin American Art

Timeline compiled by Bill Bigelow for a lesson on Burning Patience (now called The Postman) by Antonio Skármeta.

Related Resource

Democracy Now! program, Sept. 11, 2023, “The Other 9/11”: Ariel Dorfman on 50th Anniversary of U.S.-Backed Coup in Chile That Ousted Allende.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn